Introduction

In recent years, Central American refugees have become a major topic of discussion globally. The political and economic instability in the region has forced millions of people to flee their homelands in search of safety and security. The United Nations High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR) reports that the number of refugees worldwide exceeded 25 million in 2019, and currently, there are more than 3.5 million refugees and asylum seekers in the Americas alone. This article aims to explore the causes, challenges, and solutions to the current refugee crisis in Central America.

Causes of Central American Refugees

Gang Violence

Gang violence is one of the significant causes of Central American refugee crises. According to the US government, gang violence, especially in the notorious Mara Salvatrucha and Barrio 18 gangs, is rampant in the Northern Triangle countries of Honduras, El Salvador, and Guatemala. The gang activities include murder, extortion, and kidnapping, and they operate with impunity because the state is either unwilling or unable to intervene. The gangs are known for targeting young people, and they often coerce them into joining the gangs or risk death.

The US Department of State report revealed that Honduras had one of the highest homicide rates globally in 2019, with more than 40 homicides per 100,000 people. Similarly, El Salvador recorded 50 homicides per 100,000 inhabitants and Guatemala with a rate of 22 homicides per 100,000 inhabitants.

Poverty and Economic Instability

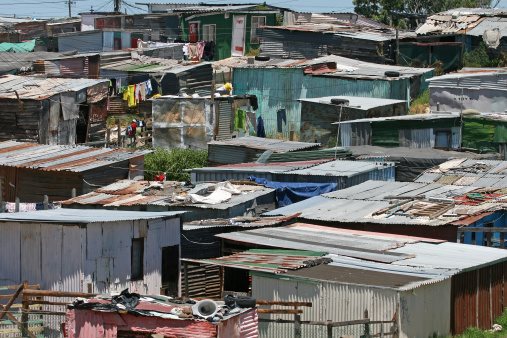

Poverty and economic instability is another cause of the Central American refugee crisis. A report by the World Bank revealed that the region remains one of the poorest in the world, with high levels of inequality and low-income levels. Poverty levels in these countries have averaged 70%, with most people living on US$2 or less per day.

The economic instability in the region is also perpetuated by inadequate job opportunities, corrupt government systems, and high levels of public debt. The UNHCR estimates that around 200,000 people migrated irregularly from El Salvador, Honduras, and Guatemala to the United States in 2019 due to poverty.

Climate Change

Climate change is increasingly becoming another significant cause of Central American refugees. The region’s environmental conditions, which have been worsened by climate change, make it more challenging to farm and harvest crops, leading to food insecurity and economic instability. The region has also experienced extreme weather patterns, including droughts and floods, thus displacing millions of people.

In 2020, Honduras suffered some of the worst hurricanes to hit Central America in decades, leading to severe flooding, landslides, and infrastructure damage. The UNHCR estimated that over 400,000 people were affected, with a significant number losing their homes and seeking refuge in shelters.

Challenges faced by Central American Refugees

Legal Challenges

Central American refugees face significant legal challenges, including geographical barriers and border security. Most of the refugees’ journeys involve crossing several countries before reaching the United States, leading to difficulties in obtaining the necessary legal documents, including visas and passports.

Additionally, border security measures, including the construction of walls, are continually used to deter immigrants from seeking asylum. President Donald Trump’s administration went further by implementing the ‘zero-tolerance’ policy, separating children from their families, and detaining them in inhumane conditions. The current US government under President Joe Biden has promised to undo some of the policies that posed legal challenges, such as revoking the travel ban on seven Muslim-majority countries and pausing deportations for 100 days.

Social and Economic Challenges

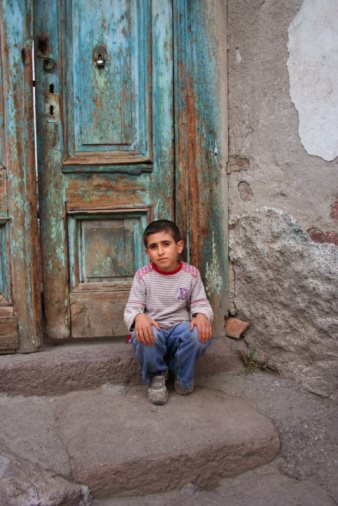

Central American refugees experience social and economic challenges, including identity fatigue, xenophobia, and lack of employment. Many of them flee from their homes with nothing more than the clothes on their backs and have to integrate into foreign societies that view them with suspicion and prejudice.

Moreover, many refugees do not have access to basic social services, including education, healthcare, and housing, which further compounds their vulnerability. According to the International Labour Organization, Central American refugees often work in the informal labor market, where they are paid less than minimum wage and subjected to poor working conditions.

Mental Health Challenges

Central American refugees often face mental health challenges, including post-traumatic stress disorder and depression, as a result of the trauma they have endured. The lack of mental health resources and support services further exacerbates their condition.

The United Nations Refugee Agency warns that the COVID-19 pandemic has made the situation worse, with increased social isolation and fears of infection.

Solutions to the Central American Refugee Crisis

Local Solutions

The Central American governments should implement policies that address the root causes of poverty, gang violence, and poor governance. This should include creating opportunities for young people, investing in education and healthcare, and increasing the accountability of government officials.

The governments should also develop more comprehensive programs that provide mental health support for refugees, particularly children. These programs must be culturally appropriate and sensitive to the unique experiences of refugees.

International Solutions

The international community should provide more assistance and humanitarian support to refugees. This could include providing additional funding to organizations such as the UNHCR and international non-government organizations that assist refugees.

Additionally, the United States has a role to play by providing temporary protected status (TPS) to refugees from Central America. TPS allows people who have been displaced by natural disasters or political instability to stay and work in the United States temporarily. Implementing TPS would help alleviate some of the legal challenges that refugees face and provide much-needed stability while they navigate the asylum process.

Conclusion

The Central American refugee situation is complex and multifaceted, requiring a comprehensive approach involving the governments of the affected countries, the international community, and civil society organizations. It is essential to address the root causes of poverty, gang violence, and environmental degradation while providing the necessary support and resources to refugees and asylum seekers. More importantly, the international community must acknowledge that refugees are human beings, and the protection of their rights and dignity should be at the forefront of any intervention.

Prior to revolution in Nicaragua in the 1970’s, the nation was under the control of Anastasio Somoza, the latest in the line of the Somoza dynasty that had held claim to Nicaragua’s leadership since the 1930’s. Somoza’s government claimed that Nicaragua was a proud champion of freedoms outlined in the First Amendment of the United States Constitution. Nonetheless, Nicaragua’s overall human rights record under Somoza was considered by many to be particularly poor, and following a major earthquake in the capital city of Managua, the situation in the country got only worse.

A declaration of martial law ensued, whereupon free press was curtailed and any opposition to Somoza’s rule was met with threats of torture and other bodily harm. The United States, who had traditionally shown support for the Somoza dynasty, rescinded any assistance to the Nicaraguan government, and in 1979, Somoza was assassinated. The Sandinista National Liberation party, a sect with Marxist ties to the Soviets, assumed power in Nicaragua.

The conflict did not end there, however. Soon, the need to depose the Sandinista revolutionaries was evident to factions within Nicaragua and the United States, as their revolution proved exceedingly bloody for those who campaigned against them.

The counter-revolutionaries, also known as the Contras, were sponsored by funding by the United States, even after foreign policy and refugee policy dictated that the Contras were not to be openly supported due to their own offenses against civilians. Pockets of armed Sandinistas and Contra rebels sprang up in other countries as well, including El Salvador and Guatemala, who were facing civil wars of their own due to capitalist-communist ideological clashes.

Many men and women refugees were caught in the collective crossfire between the Somozas, the Sandinistas and the Contras. Nonetheless, despite the weight it threw around in Central and South America, the United States was varied about the way it enforced its refugee policy, agreeing to take in Nicaraguan refugees, but often refusing Salvadorians, Hondurans, and Central Americans of other nationalities who were subject to the same persecution by Marxist groups.

This reflected refugee policy towards nations in the Western Hemisphere. Interestingly enough, however, the conflict in Nicaragua was also remembered for the role women refugees played in the fighting. Women refugees served as soldiers on both the Sandinista and Contra sides, and many of the women refugees held to precepts of feminism in the wake of their expanded role in Nicaragua’s civil unrest.